Desire Paths and Design Systems

Reducing choice and increasing options in a UI component library.February 20, 2020 · Original articleThis article was edited by Ashley Soo and originally published on Behind the Firewall, the Signal Sciences engineering blog. It was one of our most-viewed articles, and garnered attention from several prominent industry figures:

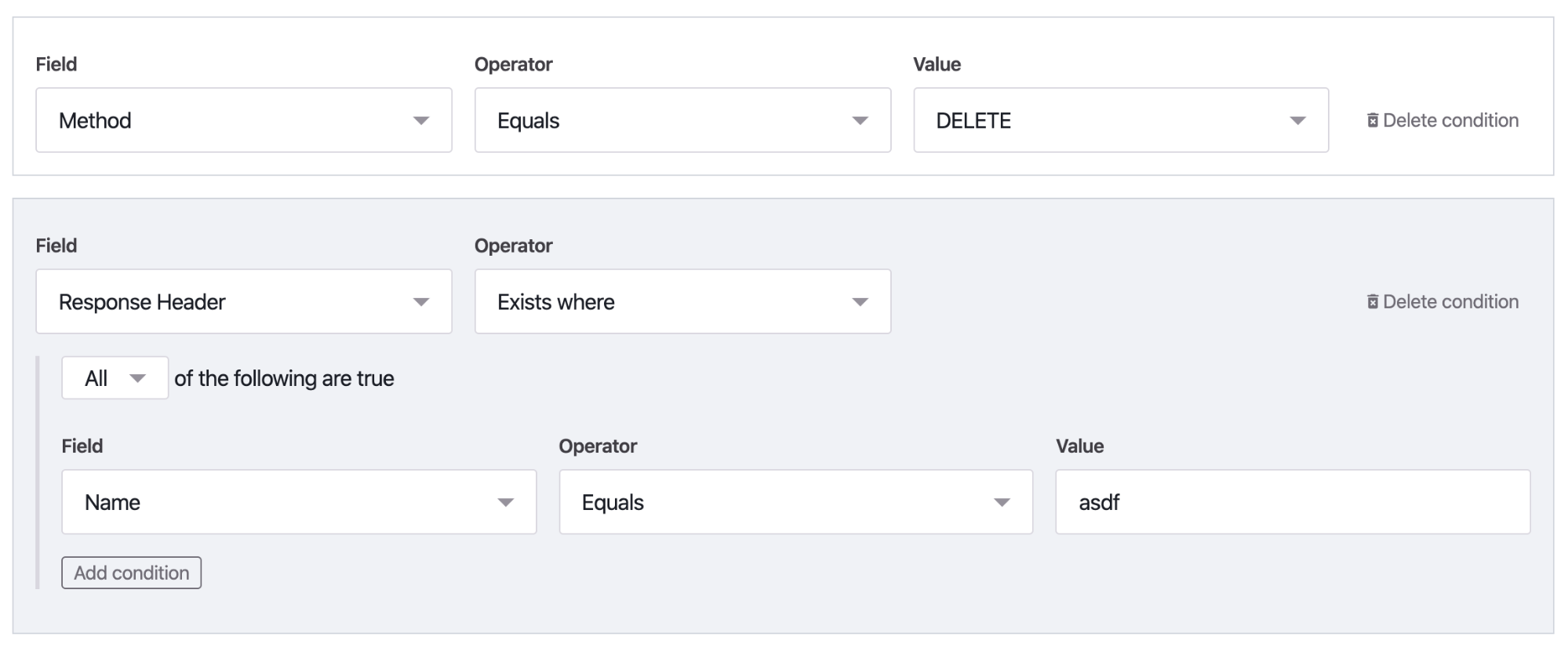

Most tech companies understand the importance of design systems by now, and we’re no different. Creating a collection of reusable and centralized components guided by a set of clear standards is a good approach to building a consistent product. At Signal Sciences, our design system exists as a set of React components called Cosmo. Our original strategy was to create unique components for each use case, and this worked well for a while. But as our UI became more complex, our designers began to feel that these components restricted creativity and prevented them from designing elegant solutions.

Our designers wanted the flexibility to create designs within the boundaries of our theme, but outside the boundaries of our existing components. They wanted the ability to bend rules, challenge patterns, and explore beyond the edges of what we had already created. To some extent they were already doing this, and so the burden of small tweaks and one-off changes often fell on the shoulders of engineers. Engineers would have to figure out how styles differ from a defined component, and then add a class and some CSS for an effective override or augmentation.

For example, The Well component (above) had opinions about backgroundColor, padding, and margin. To build this UI we had to add a border to both Wells, and remove the backgroundColor from one. This required engineers to

- Know what the defaults were

- Keep track of overrides

- Add additional styles

A better solution is to provide a generic Box component with no opinions, and allow engineers to add styles as needed.

We wanted a way for designers to feel less restricted, and for engineers to implement designs without overrides. We decided to take a new approach that allowed for greater flexibility and design freedom, while simultaneously shrinking the footprint and API surface area of Cosmo.

Introducing desire paths

This effort draws parallels to the concept of a desire path—a route that has developed over time as people walk where they see a more efficient path than the designated one. There are two ways to approach a desire path when it emerges:

- The authoritarian approach—block the desire path to force people to comply with the designated route.

- The democratic approach—listen and learn from the desire path.

Although we had built components that satisfied our explicit, current goals (a paved path between two points), our designers and engineers were making new connections and treading off the designated routes to satisfy their real, practical needs (a desire path!). Instead of taking the authoritarian approach to this transition, we pursued an engineering project to support these new paths, and even provide better tools for paths we can’t yet foresee.

Overriding default styles

Originally, we based our components on mockups, which meant they were built to satisfy current needs. Sometimes we were able to identify slight variations in a component, which we would then support with a prop. These styles were applied with classes in the component, and overrides were handled by including an additional class with its own style:

// settings.jsx

<Alert

variant="success"

className="settings--Alert"

>

Changes saved

</Alert>

// settings.css

.settings--Alert {

margin-bottom: var(--space-md);

}

New concepts become new components

As we built new features and identified new patterns, our original set of assumptions eroded and our design needs outgrew the boundaries of Cosmo. We realized that our original set of predefined components was going to cause too much manual work to keep up. Each new UI requirement meant creating a new component, with a lot of boilerplate React and unique CSS.

On top of all that, we were running into other, more subtle problems—similar concepts were captured in unique components (e.g., Section, Panel, and Well). When looking at a mockup, an engineer would have trouble making an informed decision about which component to reach for. Here’s an example of where we encountered this tension:

- If two elements needed vertical space between them, which type of container component should they be in? And further, is that even a distinction that a designer would make?

- Does a designer care if two elements are separated by a

SectionorPanel, or just that there is a particular number of pixels between them? - How should we create the space between the definition list and helper text? Do all lists have space beneath them? Is this a

Section?Panel?

Rather than continuing to create unique components for each use case, we decided that a better approach is to bake flexibility into a few basic components and allow those to be composed and remixed infinitely. We asked ourselves what really conveys the “look and feel” of a product or service—It seems to be less about the composed components, and more about the primitives of which they are composed.

The way forward

We were already working with a theme in CSS, but we shifted our focus to clean it up and provide better access to it in JavaScript. Variable and scales like fontSize, fontWeight, colors, and space all became directly available within our React components and removed the extra step of juggling classnames. Now components have reasonable default styles, which can be overridden if necessary:

// settings.jsx

<Alert variant="success" marginBottom="md">

Changes saved

</Alert>

We noticed some patterns after investigating the hacks that engineers were implementing. One pattern was that classNames were often added for small tweaks like adding or removing a default margin or changing a font size or color.

The “desire path” solution here is to provide simple primitives that allow those tweaks as first-class features. Now, for example, a Text component can be used to apply any theme color to a string. A Box component supports themed margin, padding, and border values, among others. The APIs for these components are small and reflect what designers and engineers have come to expect from CSS.

This new approach has allowed us to support fewer components, manage a consistent API, and provide designers and engineers the tools they need to explore openly and creatively without hacks and unmaintainable code.